"Extending the Synesthetic Code: connecting synesthesia, memory and art" by Dr. Hugo Heyrman March 2007, Antwerp - Belgium |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Abstract This study concerns the human experience and interrelation between synesthesia, memory and art. The aim is to outline an extended notion of synesthesia. The approach is from an interdisciplinary perspective, embedded in a context, where the senses are considered as interrelated aspects of human bodily engagement with the world. The questions I would like to focus on are: How are synesthetes 'people of the future'? What's the 'address' of the senses? What's the role of images vs. the construction of meaning, and how images are 'nomadic' in our visual memory? I want to draw some parallels between synesthesia, memory and art, towards a better understanding of the brain's natural synesthetic abilities. I will end this lecture with some remarks on five of my recent paintings. 1. Synesthesia and the future of the senses

My thesis is that all human art has a synesthetic origin, specifying the interconnectedness of existence. Synesthesia has a long history. Synesthesia is also know as 'sense transfer'. 'Cross-modal plasticity' is one of the most natural elements for all human artistic forms of creation. Synesthesia and art coexist (think with the senses, feel with the mind). Synesthesia is what makes art possible. Synesthesia and cross-modal plasticity is fundamental to human experience. Nothing in this world exists, isolated from everything else. In life everything overlaps and merges (a great undivided multiplicity is always at work). Through the interaction of our senses we are constantly engaged in a dialogue with the world. Perception is a synesthetical gestalt.

What connects synesthesia, memory and art? What are the corresponding concepts? What are the futuristic implications of synesthesia? Experiencing synesthesia, memory and art, happens in an idiosyncratic way. (3) We all have our own reality. The unique reality in every individual is based on how interactions between perceptions, desires, and expectations are formed in our neural networks. To deal with the mind-brain interaction one needs to consider the physical processes in human brains. The source of the brain’s great plasticity is called synaptic transmission. This experience-dependent plasticity, or neuroplasticity, is the ability of the brain to reorganise neural pathways based on new experiences. Neuro-imagining shows that different neurons process information at different rates: the perception of colour occurs before that of form, which in turn occurs before that of motion. Neuro-realism is based on the fact that the brain (just like the body) can't lie. The mind is what the brain does. 1.2. Neuro-privacy and brain scanning The following are the various types of brain scan systems being used today which have accelerated our understanding of the brain and the localisation of the sense and senses.

With these advanced techniques it is possible to monitor simultaneously the activity of many neurons within complex neural networks during discrete behaviors. By scanning and neuro-imaging, we can see into the workings of a human brain:

Cognitive neuroscience has come to be viewed as the flagship of cognitive sciences and is transforming our understanding of the nature of the mind. As a result of the new scanning techniques, new academic disciplines and research fields on 'mapping the mind' and mind-brain science are taking form:

Because a brain scan can tell when your paying attention to something, the scientific research on brain chemistry and neuro-anatomy has opened up new ethical responsibilities in the field of neuroscience vs. our neuro-privacy. An academic discipline of 'neurolaw' and 'neurolawyers' is flourishing. The critical questions are: "How are individual identities effected by brain scanning technology?", and "how will we integrate new neurotechnologies into our lives and social practices?". The following key terms indicate some major topics of a neurosociety: neural coding and information processing —embodiment of memory —remapping of reality —personal coding —privacy of experience. Ludwig Wittgenstein distinguishes two senses of the word private as it is normally used: privacy of knowledge and privacy of possession. Something is private to me in the first sense if only I can know it; it is private to me in the second sense if only I can have it. 1.3. The Synesthetic brain: to be a synesthete Synesthesia is a neurological phenomenon, where sensory modes blend. A synesthete's mind has the remarkable plasticity to 'taste' shapes, 'hear' colours, or 'feel' sounds. Synesthesia is genetic, synesthetes are born with it. Research suggests that it is relatively rare: it is thought that around one person in every 100 or 200 has a form of synesthesia. There are at least 50 different types of synesthesia, involving various combinations of senses both as the triggering stimulus and the secondary response (in extreme rare cases, all five senses are blended together). A returning question is: "How it must be to have synesthesia —to be a synesthete?". Synesthetes are living in a reality that others cannot experience. Most of the synesthetes I know are more "plugged in" to their environment than other people. It can be said that the brain of a synesthete is even more unique than that of a non-synesthete. Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen, synesthesia researcher at the University of Cambridge says: "If you ask synesthetes if they wish to be rid of it, they almost always say no. For them, it feels like that's what normal experience is like. To have that taken away would make them feel like they were being deprived of one sense." Uniqueness makes each of us very special, given that no one was or will ever be like us. Many writers, visual artists and musicians are synesthetes. At birth we have a raw but integrated (whole) brain to a level where synesthesia is common. We are all synesthetic to some degree, but to be a natural-born synestheste, and to experience the richness of synesthesia is indeed an extraordinary gift. The passive-active structure of world disclosure is for each synesthete a personal, complex, detailed and precise experience. In a sense, synesthetes are the people of the future, 'Homo Futuris', because with the futuristic, telematic extension of the human senses, everything will become more and more synesthetic —the senses will become 'interactive tele-senses'. (4) For example, the future libraries will become brain banks instead of book banks, synesthetic archives: an interactive multimedia integration of the visual, the kinetic, the haptic, the sonic, and the telematic. To demonstrate the state-of-the-art of the "Multi-Touch Interaction Research" hereby a short film by Jefferson Y. Han, Consultant Department of Computer Science, Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University.

These are bi-manual, multi-point, and multi-user interactions on a graphical display surface. Multi-touch sensing enables a user to interact with a system with more than one finger at a time, as in chording and bi-manual operations. Such sensing devices are inherently also able to accommodate multiple users simultaneously, which is especially useful for larger interaction scenarios such as interactive walls and tabletops. 2. Memory, an interactive storage bank of virtual possessions

2.1. Seeing, hearing, touching

To understand the wonderful complexity of our human body we have to look at the prehistory of the mind, and our connection with nature in a neurobiological sense. First of all: the human brain is wired for survival. Humans are the result of a stage of evolutionary transformations, which has lasted over two million years. Since our prehistoric ancestors developed a bigger brain, we have slowly learned how to extend our senses and how to create culture through innovations. When men created the first images, he made an important evolutionary step forward. Think about it as the invention of external memories: to store memories in the outside world instead of in their own brain (cave paintings, figurines, calendars, etc). It was also the creation of a synesthetical and metaphorical connection between time and space. Mental representations where transformed into physical ones. These representations 'detached' from external reality where fundamental for creating the kind of mind that we now have. Today, we use computers with multi-dimensional associative search engine, having an external memory. Our brains form a million new connections for every second of our lives, to make up our perceptions of the world. The external world is a physical and objective reality. The internal world is a mental and subjective reality. Key questions are: "How does our inner world influence our outer world? where does the body ends, and the world begins?" We perceive with our whole being —we see the world with our entire body sensorium. Perception is the initial point where mind and environment interact. As in seeing, we tend to hear what we expect, to hear what our memories and conditions tell us to hear. Consider the synchronisation between eyes and ear, the virtues of seeing and hearing complement each other. While the eye sees only 180 degrees, the ear hears a panoramic 360. For example: sight isolates, sound incorporates. In other words, vision is a dissecting sense; it comes from one direction at the time. Sound is a unifying sense; when we hear, we gather sound from every direction at the time. Seeing and hearing are remote senses. They tell us about distant parts of our environment by receiving vibes and waves. Seeing is also touching at distance, for example, the haptic look is a form of tactile vision; here the eye is used as an organ of touch. Haptic images are invitations to come as close as possible to the image. The word haptic is derived from the Greek term "hapthai", meaning touch —the earliest sense to develop in the foetus. Our need to touch is passionate. Touch gives an immediate communication with internal, or external bodies. Our skin is what stands between us and the world. Skin is a language; skin records the passage of layers of reality.

2.2. Tasting, smelling, remembering

Taste is a contact sense. Smell is a distance sense. Tongue and nose, they both involve a physical/chemical, intimate contact. Taste comes from the Latin word taxare, meaning "to touch" or "to feel". Of all our senses, smell is the most primal, evocative and immediate; it acts upon our body within fractions of a second, before we are aware of it. Smell can affect our mood, our emotions and the way we behave. Take cold sweat for example, which can create the smell of fear. We are also more influenced by the erotic qualities of smell than we realise. Smell has a direct access to our natural alarm system, the amygdala. The amygdala is a component of the limbic system. In evolutionary terms, the limbic system is amongst the oldest parts of the brain. Up to seventy-five percent of what we perceive as taste actually comes from our sense of smell. Taste and smell are closely coupled to memory. The main questions are:

We know that synesthesia underscores all memory processes. We also know that a richer synesthetic capacity often means a stronger, richer memory. A strong imagination and memory always employs synesthetic imagery and a metaphoric reading of life. Imagination works on memory like a flame on paper, making it glow. To some degree, the unifying function of consciousness depends on our ability to remember. As a dynamic system shaped by selection and suppression, memory provides the continuity with the immediate preceding conscious experience. New memories are powerfully influenced by old knowledge. The past imposes itself on the future. The dominant metaphor for memory retrieval is association. Remembering happens by sensory correspondences, similarities and synesthetics. Today, the term 'synesthetics' means also a new approach towards the development of the whole person with emphasis on perceptual awareness, psychological growth, self-actualization, nonverbal learning, and creative behaviour. Researchers argue that "sleep orchestrates the strengthening of memories", but also that sleep may be involved in "erasing memories from the immediate and distant past". In both cases it seems to be an ordering, a personal coding of one's stream of experiences. When a lived experience has been connected with a strong emotion, the chance is higher that it will be fused into our synesthetic memory. Flashbulb memory (the recollection of lifetime episodes via important events) is one example of this. Andy Warhol said, "Of the five senses, smell has the closest thing to the full power of the past. Smell really is transporting. Seeing, hearing, touching, tasting are just not as powerful if you want your whole being to go back for a second to something". (7) Through the power of smell, the past imposes itself on the present. This type of memory is called an episodic memory (the recollection of events). It evokes a specific experience that occurs instantly, for example, when being exposed to odour. Another type of memory associated with smell is semantic memory (the memory of facts and concepts). Semantic memory is connected with conscious thought, for example, being asked to think of what coffee or chocolate smells like. From personal memory to collective memory, from short- or long-term memory, remembering is an active and selective process of the (re)construction of the past. Memory is the capacity to bring elements of an experience from one moment in time to another. It is the unique property of life forms. 3. The synesthetic nature of painting

Art and its visual codes are human strategies of seeing and tactics of negotiating meaning. Visual thinking depends on the ability to decode and understand signification. The following five approaches are a personal source of ideas and remarks:

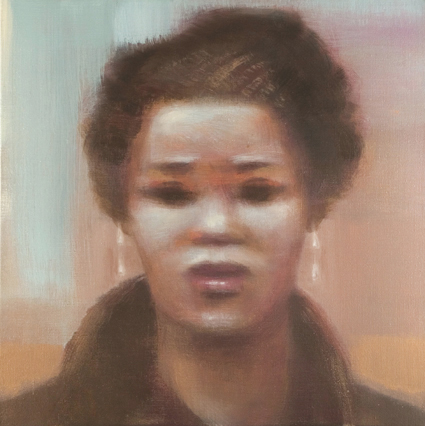

Art exist as experience. The viewer remakes the meaning of the artist. Perception is the cognitive act of projecting or creating meaning and pretending that it belongs to what is perceived. Meaning is an activity. The creation of meaning is above all embedded in human relationships and always culturally bound. In a media-dominated zap culture, the slow attention of a painting can act as a contemplative counterforce. 4. Five paintings from the "City Life & Body Language" series (8)

Context: The body language of human gestures is the first and most basic form of code, communication and information. Likewise colour is information, and consequently a powerful means of communication. Consider, for example, the colour coding of fruits and flowers (to communicate with animals) and the colours animals use for warning enemies or attracting partners. Colours are messages, like the messages of a DNA code.

Context: Psychological energy exchanges between people are far more impacting and meaningful than word exchanges. A city is especially defined by its diversity and street culture; how people differ from each other, how people use silent language and personal space. How motion precedes emotion. Up to 90% of all of our communication is nonverbal. (9)

Context: The body does not lie. The subliminal messages of the body play a major role in how we relate to others and how they see us. To define the invisible is among the strongest ambitions of human being.

Context: In the ritual quality of interpersonal actions there is a hidden code of behavioural patterns, through which hierarchical and social power structures emerge.

Context: Our bodies are the most public signals of our identities, and private reminders of who we are. We imagine by remembering or vice versa. In a landmark paper written in 1951, Donald W. Winnicott says: "It is in the space between inner and outer world, which is also the space between people --the transitional space-- that intimate relationships and creativity occur." (10) Conclusion The experience of things and thinking have to be understood as an inherently interrelated unity. Before I became aware of myself, my body already existed. The mind has no centre; the 'I' is a gestalt illusion. The 'I' is not a separately existing subject. A human is his world. I am my world. We are our world. Memory is neither a single entity nor a phenomenon that occurs in a single area of the brain. A single moment of understanding can flood a whole life with meaning. Memory is an interactive storage bank of virtual possessions. The more sensory experience you incorporate into your memories, the more likely you are to remember them. Our memory is feeding our future. Today, a synesthesia culture is taking form. Synesthesia is the future. There is a need for an extended theory on synesthesia (Synesthetics). Art reveals new synesthetic fields of experience. I believe in the exploration of new layers of reality through art. It is clear that painting can be re-invented and that it can convey conceptual content, to challenge its long history. Art connects past and future, the known and the unknown. —Dr. Hugo Heyrman Antwerp, March 2007 Ph.D. in Art sciences, painter, synesthesia researcher Professor at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp http://www.doctorhugo.org/synaesthesia/index.htm References

This research article is located online at URL:

http://www.doctorhugo.org/synaesthesia/art2/index.html Published: 2007/03/26 - 09:28:35 GMT || Museums of the Mind || |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||